Vignette No. 9: Maisons d’enfants

It wasn’t long after the liberation of our town that my uncle popped up at the Lecleres’ front door. As I’ve said before, at that time, children were not consulted about whatever adults decided to do with them. And so, without any warning that I can remember, I was whisked off by my uncle. And I don’t remember any bundle or suitcase taken along, although that may have been the case.

We took the train to Le Grand Lucé, the town I mentioned earlier, where my uncle and his family had survived the war. There, in a modest hotel retreat, he had assembled his family and my siblings. In retrospect, I assume he had wanted to reconstitute our family, such as it was. But it had been so many years since I had seen my siblings that I did not recognize them. What happened next I hadn’t expected, if I had thought about it at all.

Uncle David had a small apartment in Paris that could not have accommodated us and his family together, nor could he have afforded to feed and clothe us. So, he had contacted a Jewish social organization to perform that support. Shortly after our departure from Le Grand Lucé, we were taken to a Maison d’enfants in a town called Cailly-sur-Eure, approximately 66 mile northwest of Paris. Maison d’enfants means children’s house or home. Although it is functionally like an orphanage, it is “softer” in this case, because all the children were survivors, as were the adults who ran it.

We were in this particular maison d’enfants for perhaps a year. Why only a year? I don’t know. Perhaps the building owners wanted it back, or the funding for this particular location ran dry. Who knows? I’m just writing out loud. But then we were moved to another maison d’enfants in Jouy-en-Josas, only about 10 miles from the center of Paris. In my memoir, I speak much more of my time there, which I recollect with wistfulness, in spite of the reason that brought me there. I was in Jouy for perhaps a little less than two years, before we were moved again, this time to a village in the southwest called Moissac, near Bordeaux and about 400 miles from Paris. Quite a trip! We were housed in a rambling farmhouse on the edge of vineyards. Again, I can only conjecture as to the reason for this move. But, just like Jouy, I had fun there, romping in the fields and in the vineyards.

It might occur to you to ask why I wasn’t sad or depressed, without my parents. My answer is that children tend to live in the moment, and the disappearance of my parents had simply been suppressed. The full realization did not become front and center in my psyche till much later.

During the few years of living in the maisons d’enfants, paperwork had started to be prepared for immigration to the USA. I’m not sure when I became aware of it, but I was fully in favor of it. I think it was Uncle David who got the process started. After four years of paperwork activity, we (my siblings and me) finally received our immigration visas. There is another sub-story (not sob story) about this process that is described in my published memoir.

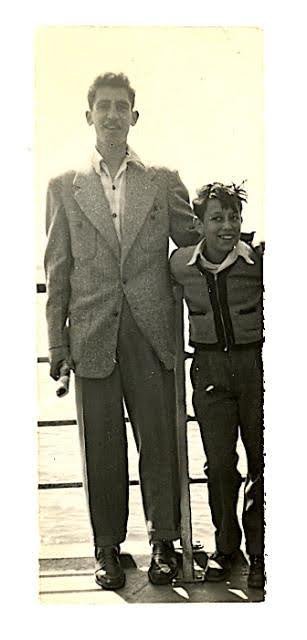

In late October 1949, Alice, Simon, and I boarded the S.S.Sobieski in Nice, bound for New York. Near the end of the voyage, someone took a photo of Simon and me on the deck of the Sobieski, from where we could see the Statue of Liberty, and in that moment, we left France behind and entered our American future.